Climate

Eastern Washington, where almost all of Washington’s wine grapes are grown, has long, warm summer days that provide ripe fruit flavors and cool nights that help lock in acidity.

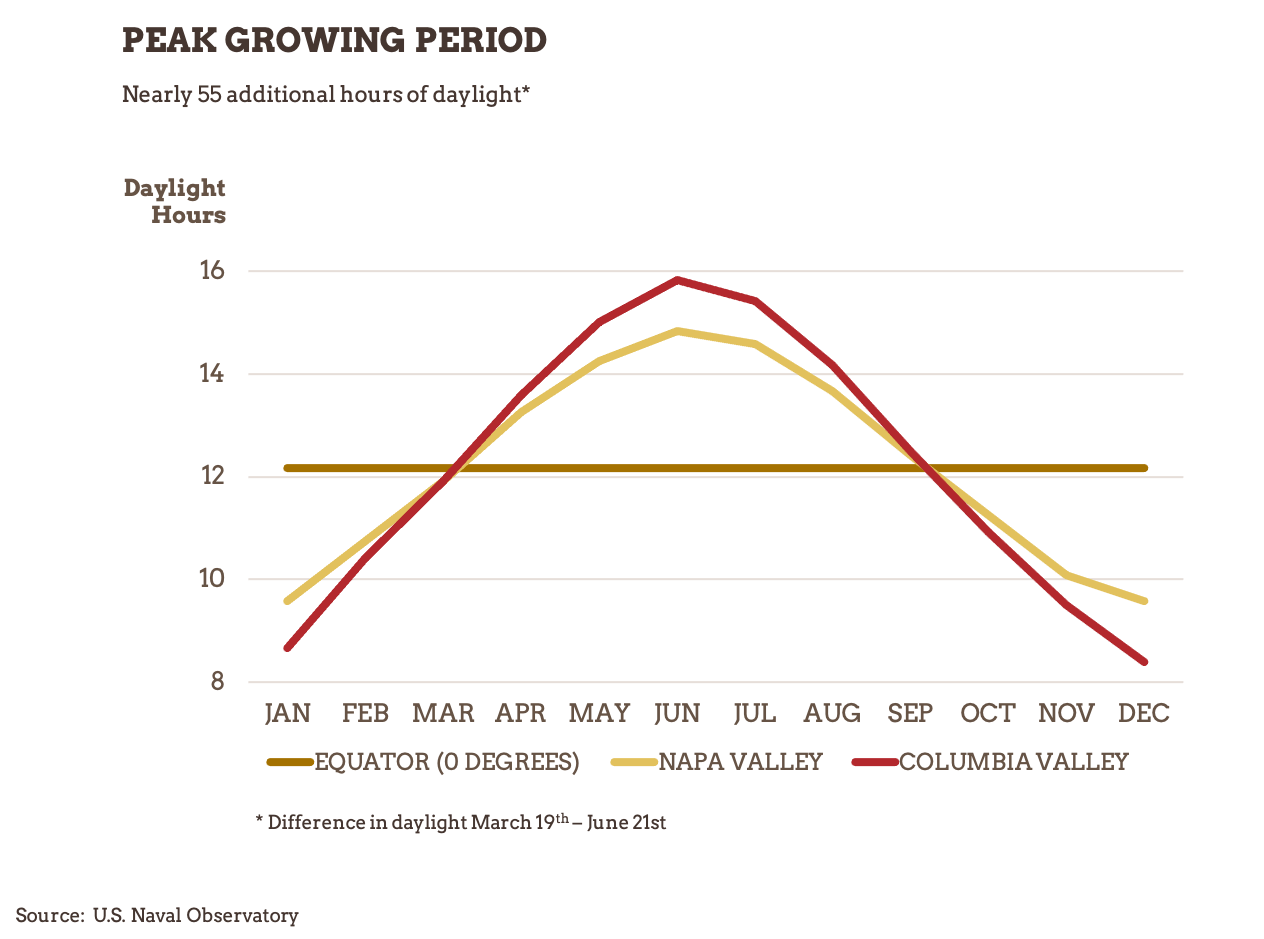

Long, Warm Days

Eastern Washington is an arid and semi-arid desert, with hot summer days. The state’s northerly latitude offers a growing season that sees up to 17 hours of sunlight a day during the summer, considerably longer than many other wine regions. Both contribute to ripe, plush fruit flavors.

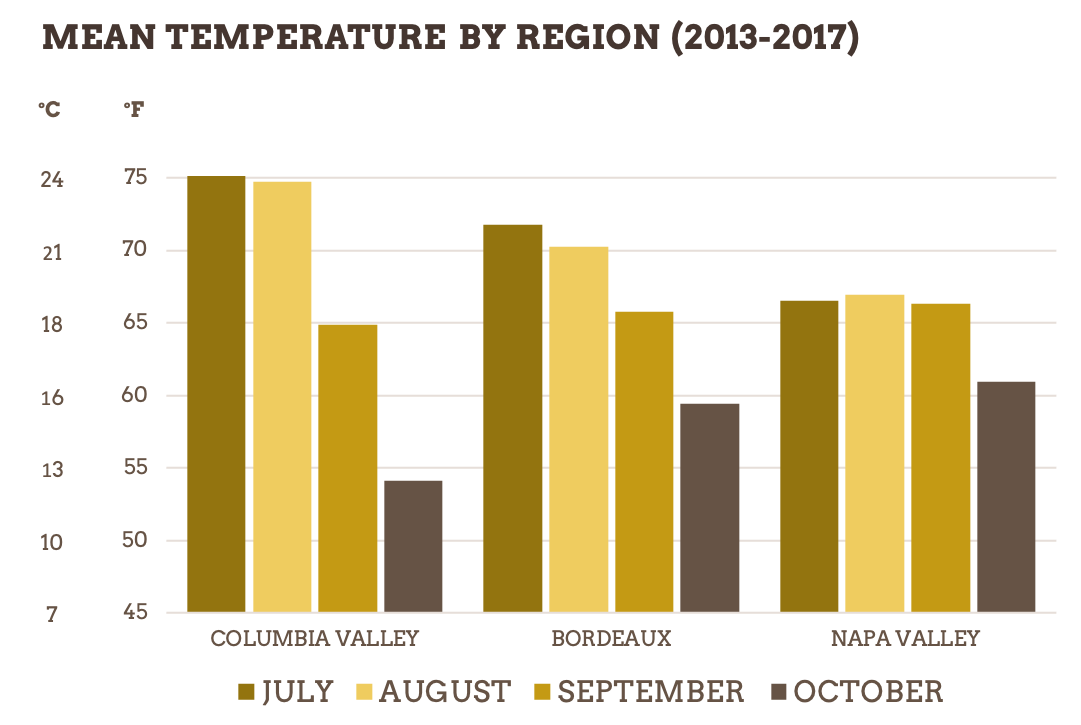

Cool Nights & Rapid Cooling at Harvest

Washington State has some of the most dramatic daily temperature fluctuations of any wine region in the world. This diurnal shift ranges from 35 to as much as 47 degrees Fahrenheit between daytime high and nighttime low temperatures. Additionally, compared to other wine regions, the temperatures in Columbia Valley cool down rapidly during harvest. Taken together, warm summer days lead to ripe fruit flavors while the large diurnal shift and rapid cooling at harvest help preserve natural acidity, creating a mixture of Old World and New World styles.

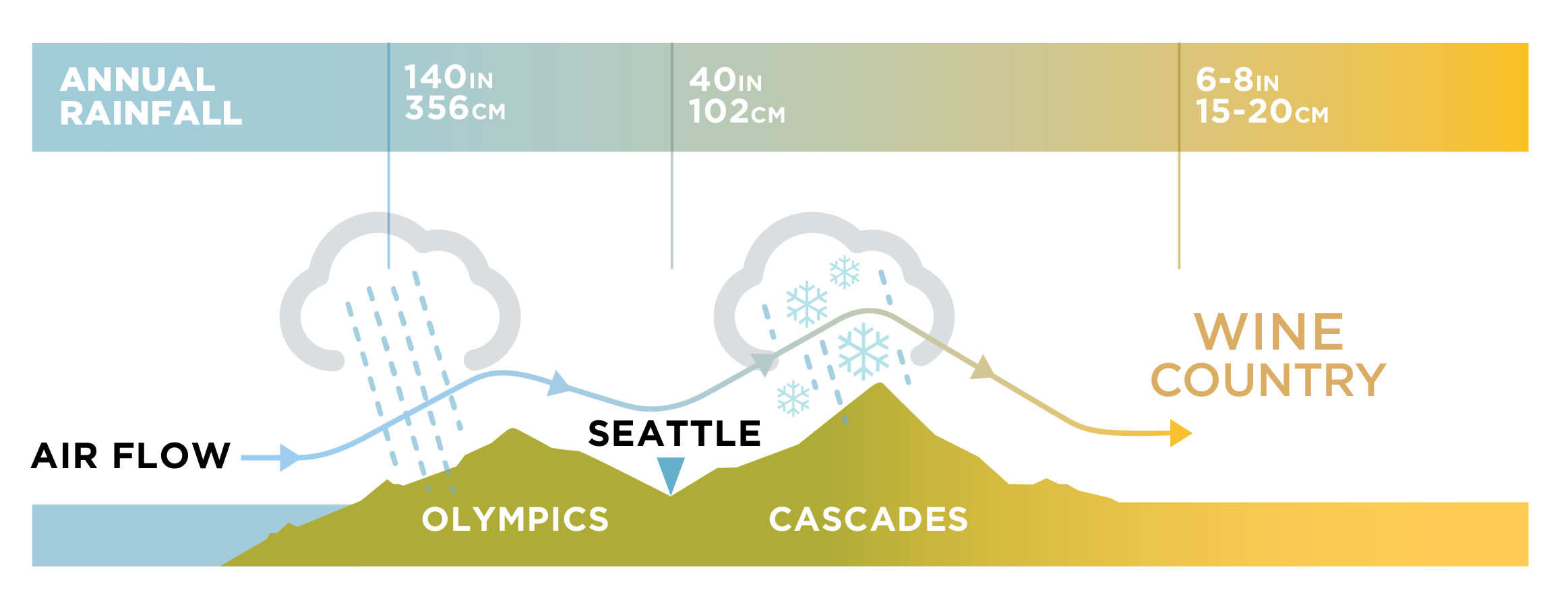

Rain Shadow Effect

The Columbia Valley is protected from wet weather systems by two major mountain ranges, the Olympics and the Cascades. Due to this rain shadow effect, Washington sees dramatically less rainfall than many other wine regions. Irrigation is therefore required in most places to grow wine grapes. This creates the perfect climate for wine in the warm, dry eastern part of the state. The use of irrigation also gives growers a high degree of control over quality.

Diversity

A large growing region, Washington is far from monolithic, with a diverse group of appellations with varying amounts of heat accumulation (Growing Degree Days or GDDs*) during the growing season, providing winemakers a diverse palette to work from. Grapes are also grown in the western part of the state, which offers a radically different maritime climate.

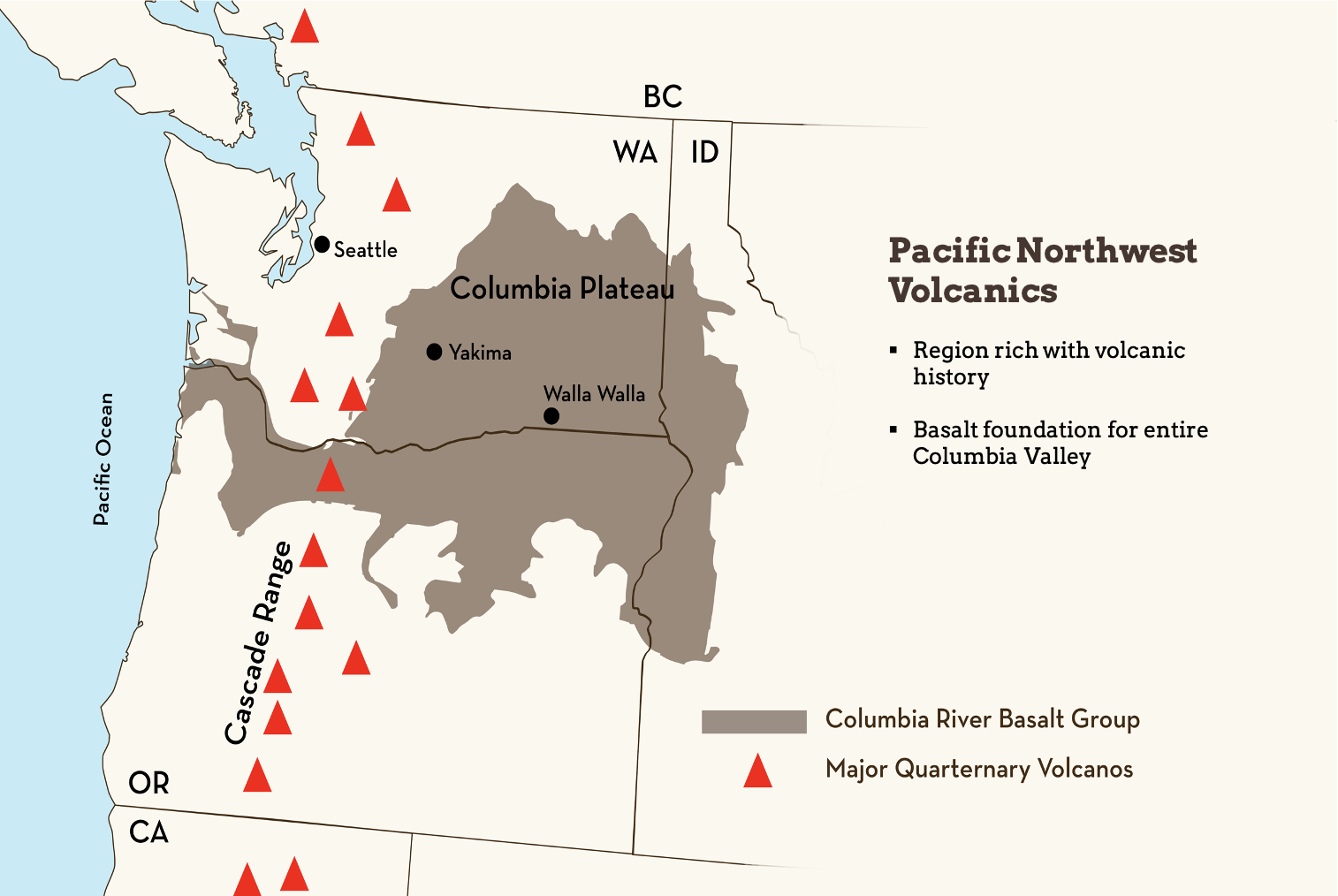

Basalt Bedrock

Millions of years ago fissures in the earth belched forth massive volumes of basalt, a dark, fine grained volcanic rock. In fact, the Pacific Northwest is home to one of the largest basalt provinces anywhere on earth, with basalt covering much of eastern Washington, northern Oregon, and western Idaho. This basalt can be thousands of feet thick, with a weight so heavy that some areas of the Columbia Basin are actually below sea level, creating a low desert environment.

Missoula Flood Deposits

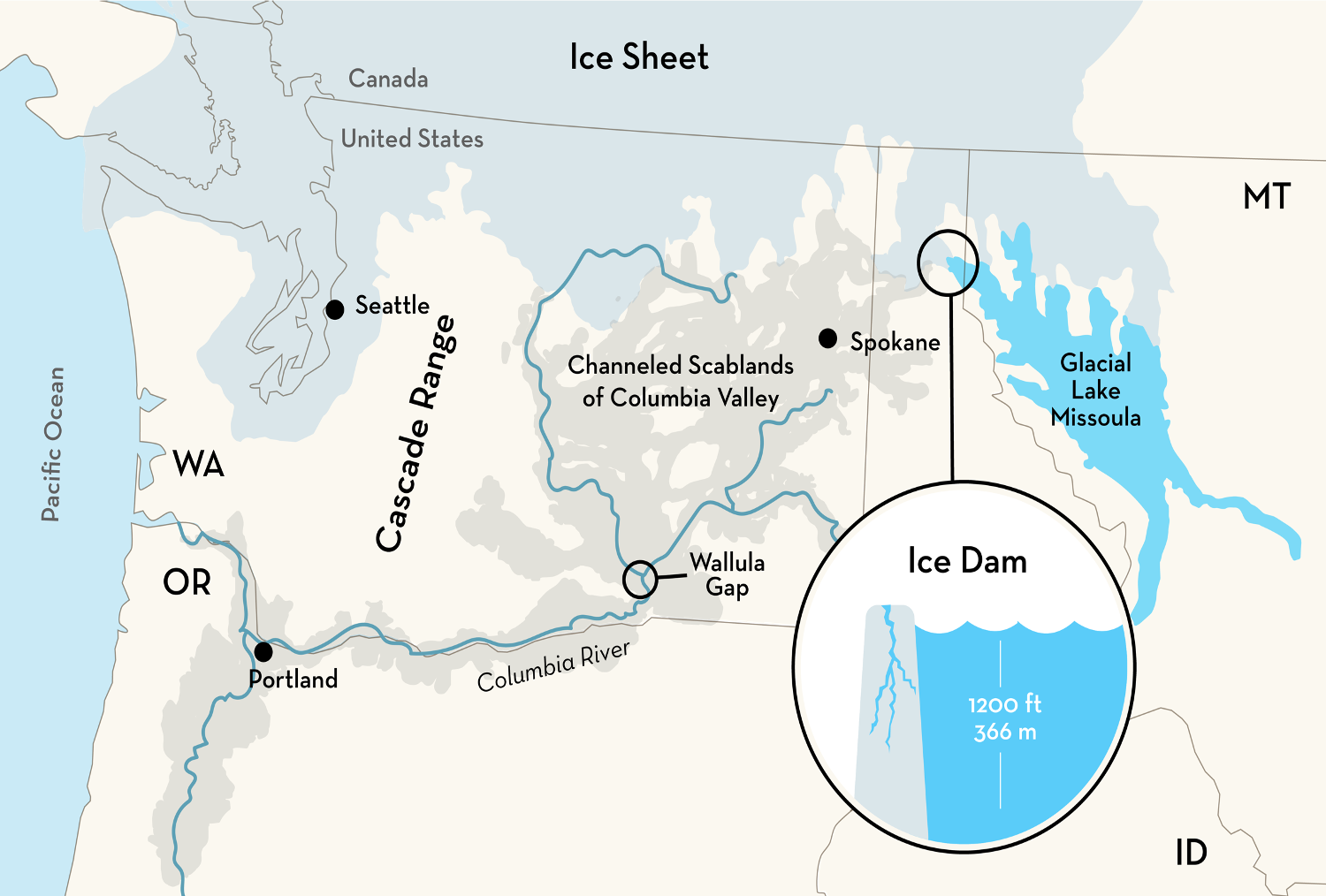

At the end of the last Ice Age, approximately 15,000 years ago, a lobe of the Cordilleran ice sheet blocked the North Fork of the Clark River in Idaho. This created a giant lake, Glacial Lake Missoula, in what is now western Montana. The dam was 1,200 feet high.

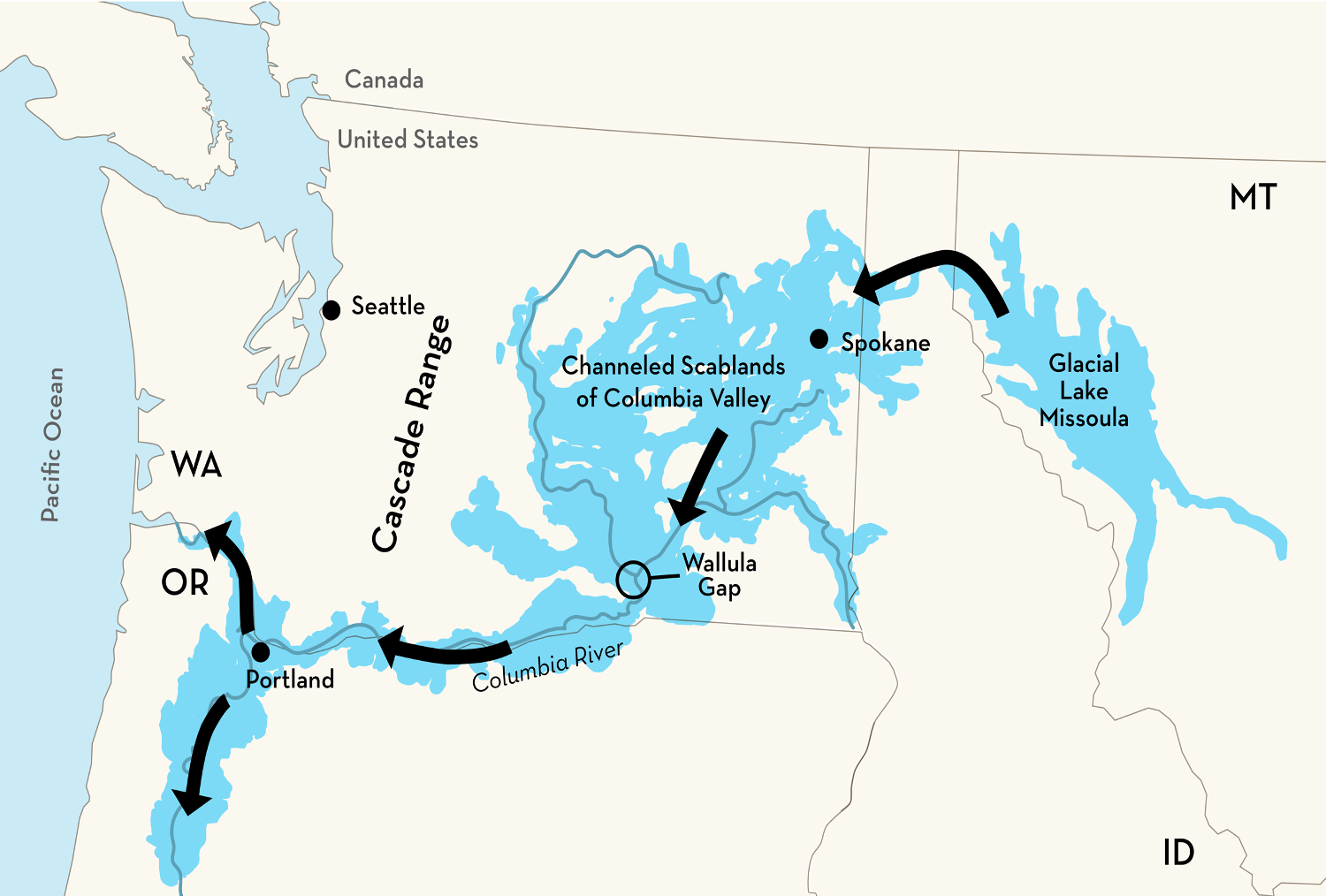

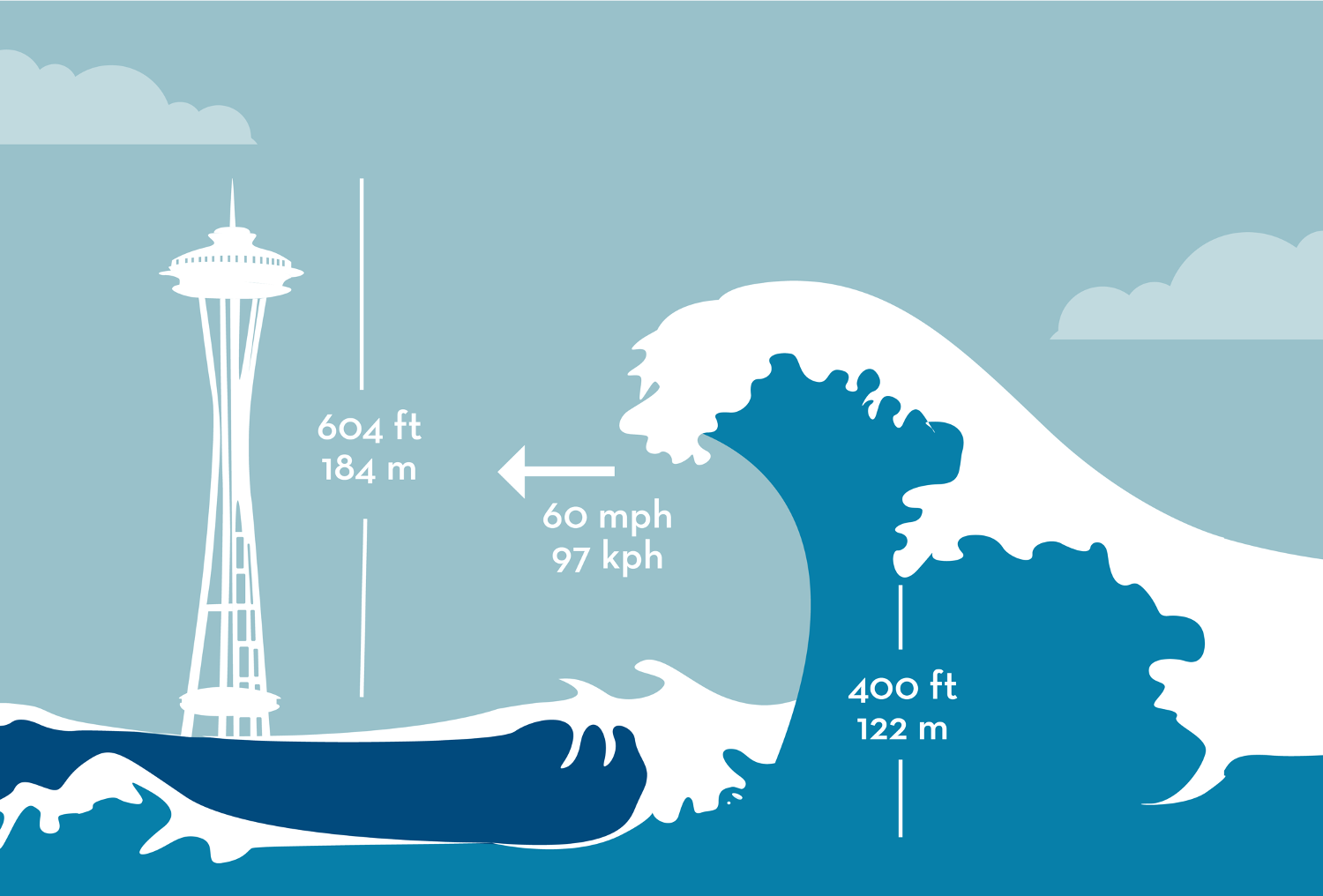

Over the course of time, the dam weakened and broke, sending a massive volume of water racing across the Columbia Valley. The floods were unimaginable in scale, with waves over 400 feet high moving at 60 miles per hour and inundating everything 1,200 feet below sea level. A pinch in the earth, the Wallula Gap, caused flood waters to back up and slowly drain. This allowed soils to drop out, heavier soils at first and then lighter soils.

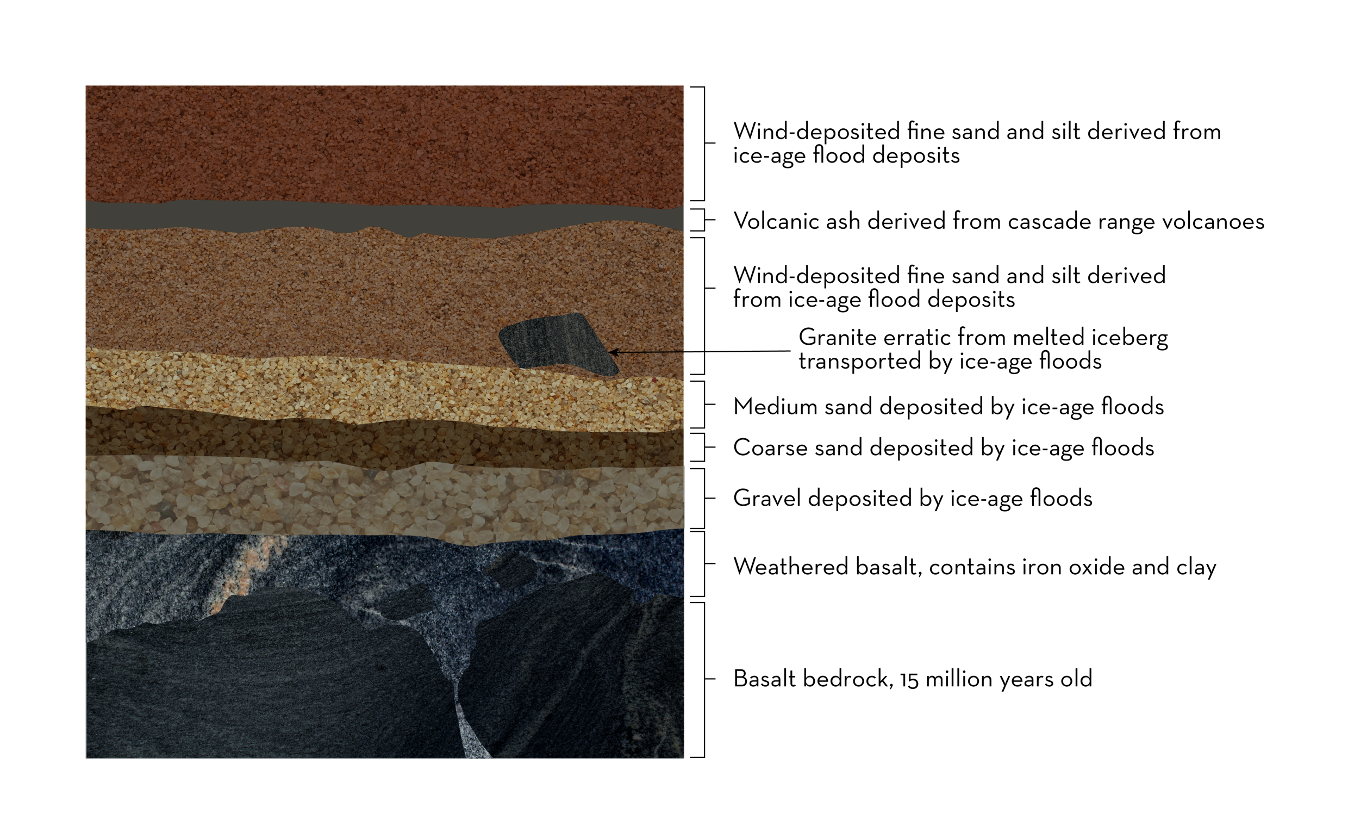

These floods didn’t just happen one time but happened a number of times over thousands of years and are collectively referred to as the Missoula Floods. This created a layer of silt, sand, and gravel on top of the basalt bedrock. These soils are collectively referred to as Missoula Flood deposits and slackwater sediments.

Loess

After the Missoula Floods ended, winds whipped through the area. This took fine sand and silt derived from these ice-age floods and over time deposited them in varying layers of thickness across the Columbia Basin. Some areas will have layers of volcanic ash deposited as well from eruptions of volcanoes. They might also have pieces of granite, erratics, brought from western Montana by the floods.

These soils, collectively referred to as loess, have low water holding capacity and are ideal for the irrigated viticulture that is the one of the bedrocks of grape growing in eastern Washington. This is why most of eastern Washington’s vineyards have cover crops. If they did not, the soils would over time blow away. The end result of all this is, below 1,200 feet above sea level, the Columbia Valley has loess of varying degrees of thickness on top of Missoula Flood deposits and slackwater sediment on top of basalt bedrock.

Yakima Fold Belt

Many of eastern Washington’s growing regions are defined by Yakima fold belt structures. These are wrinkles in the earth than create a series of syncline and anticlines. The anticlines provide south-facing exposures, ideal for growing wine grapes. Appellations on Yakima Fold Belt structures in Washington include Rattlesnake Hills, Red Mountain, Candy Mountain, Royal Slope, Horse Heaven Hills, and Columbia Gorge.

The Columbia River

Due to the fact that the Columbia Valley, where most of Washington’s wine grapes are grown, is an arid and semi-arid desert, irrigation is required to grow wine grapes in most of Washington. However, the Columbia River is the fourth largest river by volume in the United States. This and its tributaries, along with local aquifers, provide an abundance of water for the state’s vineyards.

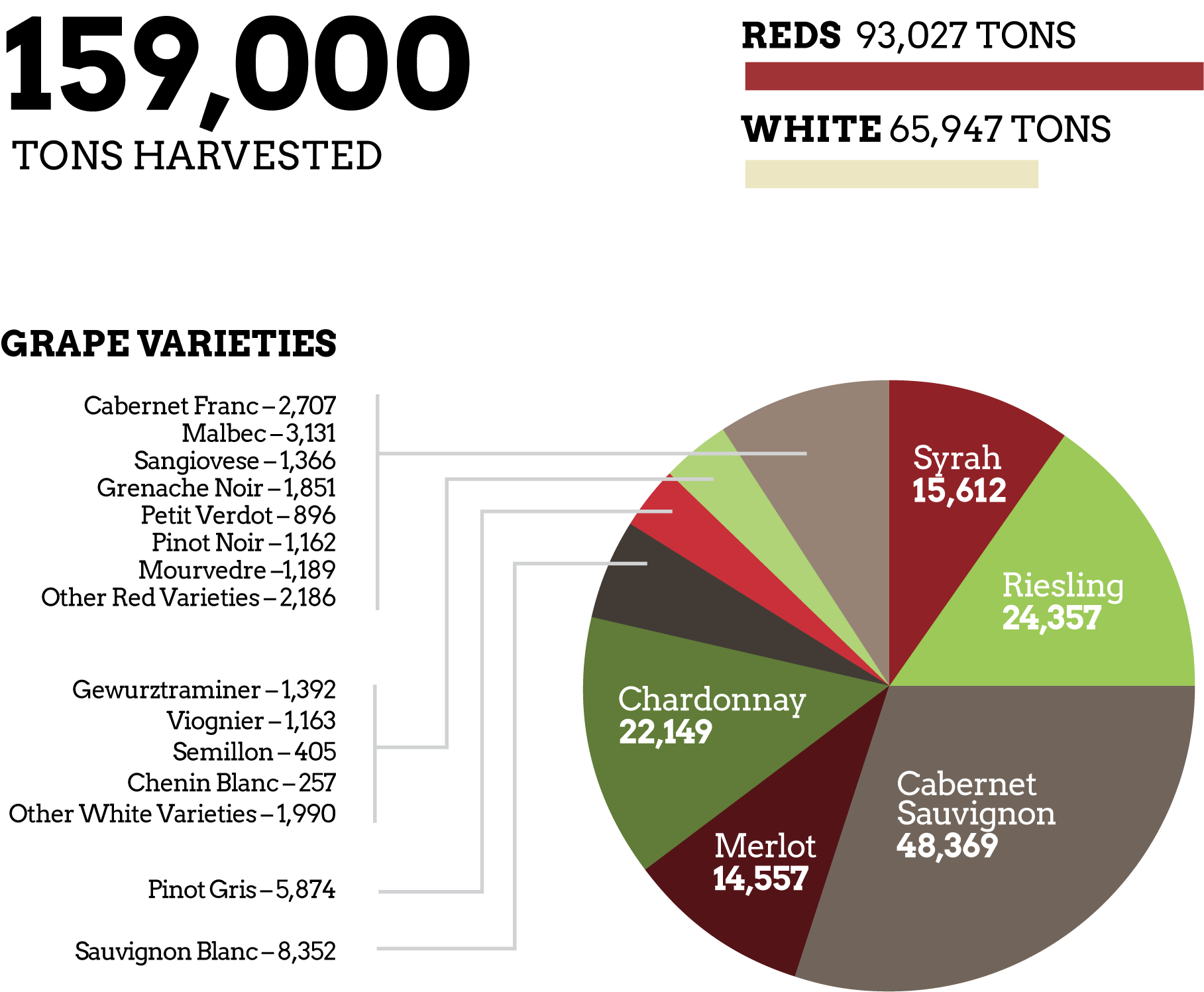

While Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, Merlot, Riesling, and Syrah make up over 80% of production each year, there are more than 80 varieties planted in the state. Many of these varieties are produced in small numbers. However, they often make some of the state’s best wines.

And below is a chart of our eight most highly-planted and highly-produced grapes, with their corresponding AVAs.

| Variety | Areas of Largest Concentration |

| Cabernet Sauvignon | Horse Heaven Hills, Wahluke Slope, Yakima Valley |

| Chardonnay | Yakima Valley, Horse Heaven Hills, Wahluke Slope |

| Malbec | Wahluke Slope, Horse Heaven Hills |

| Merlot | Yakima Valley, Horse Heaven Hills, Wahluke Slope |

| Pinot Gris | Horse Heaven Hills, Yakima Valley |

| Riesling | Yakima Valley, Ancient Lakes |

| Sauvignon Blanc | Horse Heaven Hills, Yakima Valley |

| Syrah | Horse Heaven Hills, Yakima Valley, Wahluke Slope |